Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga has been out for a couple weeks now, which means you’ve already seen it, right? If not, you’re probably the reason it’s underperforming at the box office. Don’t be the reason the new Garfield movie surpasses auteur cinema! I saw it in Portland a couple weeks ago. It was awesome. A little long, sure, and more dialogue-heavy than Fury Road- despite only 30 of those lines given to Furiosa herself. Chris Hemsworth’s rambling monologues were largely responsible for slowing down the momentum set up in its 2015 counterpart, but I was surprised by how much I missed Dementus (and his nose) when he wasn’t onscreen.

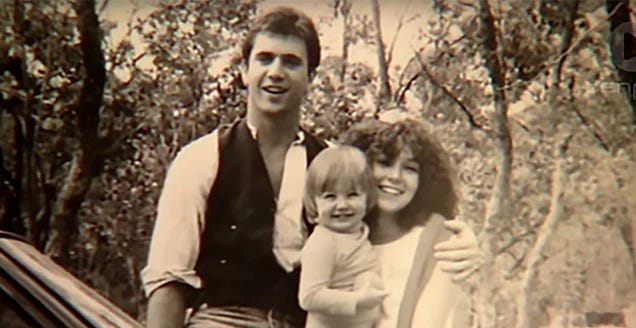

I’ve only seen the first Mad Max, but was surprised by the soft, meditative current that runs throughout the film. Mel Gibson’s Mad Max has a loving relationship with his wife and child. He has a best friend. He literally goes on vacation. His partner and child go get ice cream. Of course, this is in between bonkers car chases and grotesque injuries. But I never would have guessed that the heartbeat of a Mad Max movie is family. I found the first half of Furiosa to be stronger than the second half. And it’s precisely because of the warmth between Furiosa and her (hot, very cool) mother. The ensuing revenge story was really fun, but the story lingers because of its emotional core.

But we’re not here to talk about the Mad Max saga are we? I wanted to look outside of George Miller’s more profitable heroes and discuss two films that showcase just how mulitfaceted the director can be.

The first is 1987’s Witches of Eastwick, which is one of my favorite movies to recommend to anyone for any reason ever. It’s based on a John Updike novel, taking place in the idyllic New England town of Eastwick. It’s the kind of town I imagine is in a perpetual state of autumn- the trees are always a rusty orange, pumpkins adorn deteriorated porches, and the grocery stores are stocked with fresh apple cider. You’re in danger of running into Stephen King every time you turn a corner. You know the type! This is the sort of town we meet our protagonists in. They are Susan Sarandon as Jane, Michelle Pfieffer as Sukie, and Cher as Alexandra with the type of bouncy, gravity-defying hair that does not exist outside of the magic of the movies.

All three of these gorgeous, talented women are recently single. Hard to believe, but this is the first of many, many times you will be asked to suspend your disbelief at the chaos unfolding onscreen… and I promise you it is worth it. We are introduced to the three friends at one of their drunken girls nights, where they share what they’re looking for in their ideal man. I shit you not, this is part of that conversation:

Sukie: Huge.

Jane: I prefer small.

Sukie: Oh, yeah, right.

Jane: No no no, Sam was huge, and there were times when I just could not face it.

Alexandra: Really? Well, I’m sort of in the middle myself. But hey, as long as it works, it’s in.

I am obsessed with this. I’m not sure if John Updike or screenwriter Michael Cristofer is responsible for this dialogue, but it’s very clear to me the dick sizes we’re working with on this production.

Over the following days, we learn that a mysterious man has purchased a mansion in town previously rumored to have burned witches. The stranger appears at one of Jane’s music recitals and causes quite the stir when he falls asleep. The stranger in question is…. Jack Nicholson! His name is Daryl Van Horne, and the hellish antics don’t stop there. Our three heroines meet, and inexplicably fall for, the grotesquely charming Daryl. You know, despite the fact that Nicholson’s hornlike hairline and devilishly arched eyebrows might indicate that he most likely also answers to the name “Satan”.

The girls and Van Horne enter into a polygamous relationship from hell, and it’s totally unhinged. The magic of how this relationship came to be is a little unclear- the girls must’ve activated their powers by coming together and speaking their desires into being? Who cares! The hijinks never cease when the girls move into Van Horne’s mansion and the relationship sours. You know, when the trio starts to suspect the creepy man that appeared out of thin air might not be the dreamboat he professed to be. No spoilers, but Cher delivers a blow to Nicholson that every girl has thought but couldn’t articulate. Girl Power! There’s an excessive amount of cherry pits puked up, angry churchgoers, fiery cellos, a tennis game that challenge(r)s the laws of physics, and Jack Nicholson in a pink suit. And that’s like 10% of the chaos! Of course, all demonic dalliances must come to an end, and said ending does not disappoint.

I want to share more, but it’s a film that needs to be experienced to be believed. I probably could have just shown you this picture and saved myself the typing:

The Witches of Eastwick (1987) is currently available to rent.

Pivoting hard here to talk about another (excellent) George Miller/Susan Sarandon vehicle. Based on a true story, 1992’s Lorenzo’s Oil follows the Odone family as they navigate insurmountable grief after their son Lorenzo is diagnosed with a rare, terminal neurological disorder. We first meet the Odones in Africa- Nick Nolte is Augusto, the patriarch whose position at the World Bank has them stationed in the Comoro Islands. Michaela, played by Susan Sarandon, is the fiercely intellectual matriarch. Soon after the Odones move back to the states, their son Lorenzo begins exhibiting baffling symptoms. Lorenzo’s teacher Laura Linney (in her first role!) pulls Michaela aside after school one day. Lorenzo has been throwing tantrums, hurting the other children. She asks about trouble at home. Michaela is shocked- nothing is wrong at home- Augusto and Michaela are happy, Lorenzo is a perfectly well-behaved seven year-old. But things get worse: Lorenzo becomes clumsy; he listens to music at full volume and even then positions himself directly in front of the speaker; his tantrums begin to manifest at home. Lorenzo was a bright child- multilingual from his time abroad, curious and friendly. He is now a fraction of himself. Augusto and Michaela subject their son to extensive testing. The only certainty is that something is very seriously wrong with their son.

Finally, the doctor calls Michael and Augusto into his office. He’s uncomfortable, fumbling with the air conditioning and fidgeting. He circumvents the diagnosis, until Augusto stops him and asks the doctor for it straight. “Without equivocation.”

We learn that Lorenzo has been diagnosed with adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), which is as bad as it sounds. Essentially, ALD is the accumulation of long chain fatty acids in the body. It most devastatingly affects the central nervous system and the neurons in your brain. The doctor tells us that it presents exclusively in very young males, and the prognosis is two years. The disease is too rare, and nobody has done the research to provide adequate treatment. Augusto and Michaela accept the news with a grim resolve, Michaela’s wobbly voice the only indicator of her terror. They leave the office, Michaela clutching her only son’s sick body to her chest.

There is a scene soon after the diagnosis where Augusto is in the library reading about ALD. Scary words like “seizures” “blindness” “paralysis” and “death” flash across the screen. The look in Augusto’s eyes is half-crazed with grief. He walks down the stairs at the library, panting and fumbling. He falls and crumbles under the weight of his son’s suffering, animalistic cries of anguish piercing through the stifling, cramped stairway. He writhes from the pain; in a worse movie, this expression of grief would be corny, too much. But we understand that Augusto’s father has seen into the future, and it is hopeless.

It was around here where I questioned why George Miller wanted to make this movie in the first place. This is the man that has brought us everything from Mad Max to Babe to Happy Feet. Why make a medical drama? But then I remembered that George Miller is a doctor. He’s been in these rooms with helpless patients and even more helpless loved ones. He’s seen euphoric recoveries and devastating losses. George Miller is actually perfectly qualified to tell the story of a family navigating medical adversity. Miller does this best when we’re in the doctors’ offices and the Odones are asking questions the doctors don’t have answers to. When the Odones ask why nobody has bothered researching such a deadly disease, the doctor reminds them that it’s simply too rare. Nobody wants to fund research for a disease that affects such a small portion of a population when things like cancer exist. The doctor is not unkind, he’s simply practical. This is when the Odones decide to take matters into their own hands. The fact that they’re naturally intelligent and diligent helps, but they aren’t doctors. This also seems to benefit them- they aren’t limited by years of theory and soul-crushing protocol and can think outside the box.

My favorite scenes are the ones where Michaela and Augusto have epiphanies through ordinary means. After hours bent over medical texts, Michaela runs home with the realization that Lorenzo’s bland diet might be causing an overproduction of fatty acids. Through a kitchen sink metaphor, Augusto is able to present an idea about creating an oil that halts this overproduction. The medical bureaucracy and governmental hoops they need to jump through proves difficult, though, and Lorenzo continues to deteriorate. He can’t even swallow his own saliva; a nurse needs to sit with him 24 hours a day to suction the liquid out before it reaches his lungs. There is a heartbreaking moment where the Odones ask themselves if all of this work is going to be for the benefit of other kids- Lorenzo will likely not live long enough to reap the fruits of their efforts. Another moment (where I allowed myself a thirty second ugly sob while my boyfriend was in the other room) questions whether it might be best for Lorenzo to just die instead of prolonging his suffering.

The film is triumphant; flailing; joyful; hopeless. Every small victory is euphoric while every setback is anxious and dreadful. It is sincere and funny at times- Nick Nolte’s Italian accent is confusing at first but grows on you. Susan Sarandon is steadfast and grimly optimistic throughout. She is uncertain of the future but totally convinced that her son is in there somewhere, and so we too are convinced. With Lorenzo’s Oil, Miller shows us that he doesn’t have to resort to the fantastical to tell a fantastic story.

Lorenzo’s Oil (1992) is currently available to rent.